I research philosophy of mind applied to AI.

In broad strokes, I’m interested in whether AI could have morally significant mental states. Does it feel like something to be chatbot or agentic AI? Is the character of those experiences positive or negative? In particular, I am advancing our understanding of:

- The evidence for robot pain.

- Mechanistic methods for assessing AI consciousness.

I am supervised by Matt Parrott and Brad Saad. I have some early drafts available upon request.

In 2023 I worked on a policy report with researchers at Longview, giving ballpark estimations for the cost of solving major problems.

Fin Moorhouse, Riley Harris, Tyler M. John, Kit Harris, & Natalie Cargill (2023). What if the 1% gave 10%? Longview Philanthropy Technical Report.

Abstract

Our hope in this report is to show the potential of another kind of philanthropy. We show what one version of ambitious philanthropy could look like: how it could enable projects to begin solving serious global problems, and ignite optimism about the potential to make a real—and very big—difference through giving.

So we asked: what if the global 1% gave just 10% of their income in such an ambitious way? And, for those whose wealth outstrips their income, what if they gave just 2.5% of their net worth, aimed at making real progress? What could such a level of giving achieve?

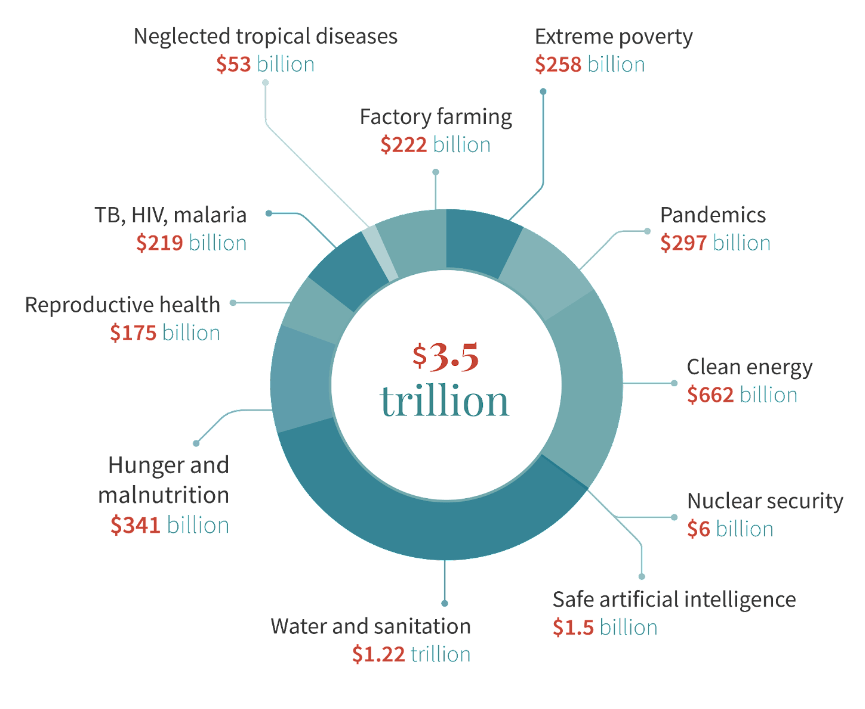

The answer is surprising: in just the first year, this would result in an increase of at least $3.5 trillion over and above what already goes to charity each year. If these resources were deployed to solve some of the world’s most pressing problems, in just one year we could achieve the following:

- Ensure no one in the world lives in extreme poverty for that year, and lift millions out of poverty for good.

- Prevent the next pandemic.

- Double global spending on clean energy R&D until 2050.

- Quadruple philanthropic funding for nuclear weapons risk reduction in perpetuity.

- Increase tenfold the funding for projects ensuring advanced AI is safe and beneficial.

- Ensure everyone has access to clean water and sanitation, once and for all.

- End hunger and malnutrition.

- Give women control over their reproductive health by funding contraception, maternal care, and newborn care for all women for at least 5 years.

- Massively suppress or eradicate tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV.

- Massively suppress or eradicate most neglected tropical diseases.

- Halve factory farming by 2050.

In 2022 I completed my MPhil by publication at Adelaide:

My thesis, Normative Uncertainty and Information Value, was supervised by Antony Eagle and Garrett Cullity. I went on to begin graduate work with Teru Thomas at Oxford, but felt compelled to refocus my graduate work.

Abstract

This thesis is about making decisions when we are uncertain about what will happen, how valuable it will be, and even how to make decisions. Even the most sure-footed amongst us are sometimes uncertain about all three, but surprisingly little attention has been given to the latter two. The three essays that constitute my thesis hope to do a small part in rectifying this problem.

The first essay is about the value of finding out how to make decisions. Society spends considerable resources funding people (like me) to research decision-making, so it is natural to wonder whether society is getting a good deal. This question is so shockingly under-researched that bedrock facts are readily discoverable, such as when this kind of information is valuable.

My second essay concerns whether we can compare value when we are uncertain about value. Many people are in fact uncertain about value, and how we deal with this uncertainty hinges on these comparisons. I argue that value comparisons are only sometimes possible; I call this weak comparability. This essay is largely a synthesis of the literature, but I also present an argument which begins with a peculiar view of the self: it is as if each of us is a crowd of different people separated by time (but connected by continuity of experience). I’m not the first to endorse this peculiar view of the self, but I am the first to show how it supports the benign view that value is sometimes comparable.

We may be uncertain of any decision rules, even those that would tell us how to act when we face uncertainty in decision rules. We may be uncertain of how to decide how to decide how to… And so on. If so, we might have to accept infinitely many decision rules just to make any mundane decision, such as whether to pick up a five-cent piece from the gutter. My third essay addresses this problem of regress. I think all of our decisions are forced: we must decide now or continue to deliberate. Surprisingly, this allows us to avoid the original problem. I call this solution “when forced, do your best”.

(Summary)

This page was updated in February 2025.